ON 6 October 2013 doctor and volunteer trade unionist Neil Aggett would have celebrated his sixtieth birthday. Instead, half a lifetime ago, he died on 5 February 1982 at his own hand in a cell at Johannesburg’s notorious John Vorster Square police station at the age of just 28. A political detainee under the Terrorism Act, he had been in solitary confinement for more than two months, and a few days prior to his death he was subjected to intensive interrogation lasting over 60 hours. His was the 51st death in detention; the first of a white person; and his life and tragically early death contain truths about South Africa past and present that still engage us today.

ON 6 October 2013 doctor and volunteer trade unionist Neil Aggett would have celebrated his sixtieth birthday. Instead, half a lifetime ago, he died on 5 February 1982 at his own hand in a cell at Johannesburg’s notorious John Vorster Square police station at the age of just 28. A political detainee under the Terrorism Act, he had been in solitary confinement for more than two months, and a few days prior to his death he was subjected to intensive interrogation lasting over 60 hours. His was the 51st death in detention; the first of a white person; and his life and tragically early death contain truths about South Africa past and present that still engage us today.

For years there has been speculation about precisely why a committed, determined idealist like Aggett would commit suicide. The prisons service bears heavy responsibility. He had complained to the visiting magistrate about assault and torture, but no action was taken. And he appeared to have a left a symbolic message: on the floor of his cell was a copy of Zorba the Greek open at the page about a suicide. This was doubly poignant as George Bizos was to be the family’s inquest lawyer.

At the Truth Commission two security policemen applied for amnesty for his torture, and for burgling his home and supplying misinformation. The apartheid state and high-ranking police officers were found responsible for gross violations of Aggett’s human rights that led to his death. However, the only hope of a glimmer of truth about his last days in that perverted world of detention, questioning and statement writing lies with his security branch interrogators, Major Arthur Cronwright and Lieutenant Stephen Whitehead. As Nalini Naidoo, an activist of that period, points out some white detainees were regarded as ethnic traitors and given a particularly hard time.

Minister of Justice Jeff Radebe has recently revealed that his department is considering prosecuting them both, presumably for culpable homicide, as neither applied for amnesty. The Hawks are investigating. It is a chilling reminder that psychopaths from the apartheid system remained at large: a senior security policeman told Bizos that Cronwright was regarded even by the system as a madman. However, as the Independent Police Investigative Directorate has just reported, people continue to die in numbers in police cells. Torture has only recently been specifically prohibited in law.

Aggett’s death proved the point made repeatedly at the time that prolonged detention without trial is a form of psychological torture, a fact skillfully used by Bizos at the inquest. In the words of Helen Joseph ‘it was a mirror held up to reflect the unimagined depths of depravity, brutality and destruction’ practised by the apartheid state. But Bizos believes that adverse publicity about detention ushered in the era of the death squads: assassination and disappearances that required no explanation in any court and could be blamed on all manner of causes.

As a qualified doctor, Aggett’s work at hospitals such as Tembisa and Baragwanath and in Transkei convinced him of the need for a holistic view of medicine that took into account social context such as poverty, poor wages and unemployment. Industrial injuries were a particular feature of his work. Moving to Johannesburg in the mid-1970s he came into contact with trade unionists like Gavin Andersson and Sipho Kubeka, who had links with the South African Congress of Trade Unions. He also became part of the city’s radical communal life at Crown Mines characterised by gardening, woodworking and the ubiquitous reading and discussion groups.

Aggett’s approach to trade unions straddled the ideological divide of the time. A supporter of industrial unions that placed worker interests at the forefront by operating within the law and exploiting every opportunity it offered, he was also attracted by experience to the idea of political unions that created links with surrounding communities. He was later to work with the South African Allied Workers Union, but he was well aware of the danger posed to labour by external pressure and manipulation. Day-to-day accountability and democratic process were then, as now, critical. As a medical activist he was concerned with workmen’s compensation issues, and convinced of the potential for an advice office function and medical schemes within the unions. The issue of rights and respect in the workplace remains with us today: Aggett’s mission was to rid the employment arena of the old master and servant relationship.

His initial contacts with the unions were unsuccessful, but he was eventually recruited by Jan Theron and Oscar Mpetha as a volunteer organiser for the unregistered African Food and Canning Workers Union in Johannesburg. Aggett played a significant role in the Fattis and Monis strike of 1980. This not only signified solidarity between coloured and African workers, but drew in students, community groups and even traders, and after six months forced the company into an historic agreement that admitted recognition. The Wilson Rowntree strike was to follow. Such pressure sounded the eventual death-knell of the liaison committees and industrial councils used by government and employers to minimise employees’ rights. At the time of his death Aggett was involved in the process of convergence between the political unions and the workerist affiliates of the Federation of South African Trade Unions.

Aggett’s medical and union roles showed exemplary service in the cause of oppressed people. Having worked nights at Baragwanath Hospital (he was an expert on emergency resuscitation), he then spent his days on union work, an extraordinarily punishing lifestyle. This was the world of the Left in which personal life was often, and unreasonably, seen as an indulgence. Such dedication led some to believe mistakenly that Aggett was a Communist and working as an underground operative. A humble, introspective and altruistic person, he moved, in the view of his biographer Beverley Naidoo, beyond the boundary of the white South African Left and was becoming assimilated into the life of the African working class. This could have been a reason why he was of such particular interest to a paranoid police security branch obsessed by a supposed mass conspiracy waiting for exposure.

The apartheid state believed, perversely and tragically, that it could kill ideas by killing people. Aggett was not the first victim. Apartheid had already murdered Ahmed Timol in 1971, Steve Biko in 1977 and Rick Turner in 1979; and would do the same to Matthew Goniwe in 1985 and David Webster in 1989. What they all had in common was a single-minded commitment to the ideals of a free and democratic society and their achievement through non-violent organisation and peaceful persuasion.

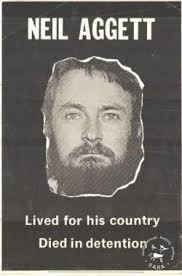

Aggett’s world was cerebral, but his thinking led him into remarkable practical action in the inter-connected worlds of medicine and worker organisation: praxis in the terminology of the Left. As a poster said at his funeral, he died for his ideals: ‘lived for his country; died in detention’. But perhaps David Dison moves closer to the truth: ‘Honesty killed him’.

In a world of largely orthodox thought and rampant dishonesty of various hues, Aggett’s short but ultimately influential life requires and deserves lasting commemoration and reflection.

This article was first published in The Witness on 7 October 2013 and entitled ‘Honesty killed him’.

Further reading: Beverley Naidoo, Death of an Idealist: In Search of Neil Aggett (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2012).